Van der Waals’ forces

Van der Waals’ forces (‘Waals’ is pronounced ‘varls’) are forces of attraction between a temporary dipole on one molecule, and an induced dipole on another molecule. They occur between both polar molecules and non-polar molecules, but they are more important in nonpolar molecules.

Temporary dipoles

The electron cloud around an atom or a non-polar molecule is not static. On average it is distributed evenly, but small changes in its distribution happen all the time. Changes like these cause a temporary dipole. This is very short-lived and may disappear in the next instant. Temporary dipoles are different from permanent dipoles, which exist continually because of a difference in electronegativity between the two atoms in a covalent bond.

Induced dipoles

The appearance of a temporary dipole in one molecule can cause a dipole to form in a neighbouring molecule. This is called an induced dipole. It is opposite in direction to the temporary dipole that induced it. The opposite partial charges attract each other, causing an attractive intermolecular force.

The strength of van der Waals’ forces

The strength of van der Waals’ forces increases if the following increase:

- The size of the atom or molecule

- The area of contact between molecules

Size of the atom or molecule The elements in Group 0 are all gases. As you go down the group, the atomic number increases and so does the number of electrons in each atom. A xenon atom near the bottom of the group is larger than a helium atom at the top. It is more easily polarized. Temporary dipoles form more readily in xenon, and dipoles are more easily induced in neighbouring xenon atoms. The van der Waals’ forces between xenon atoms are stronger than those between helium atoms.

You can see a similar trend in the boiling points of the Group 7 elements. These exist as diatomic molecules, but as the atomic number increases so does the boiling point.

Area of contact between molecules

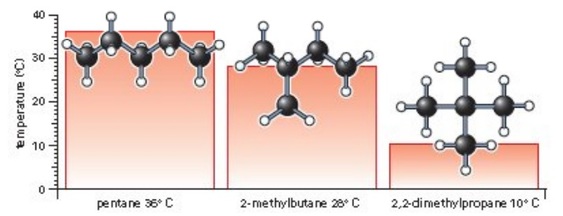

The greater the area of contact between the molecules, the stronger the van der Waals’ forces become. You can see this if you study the effect of having a branch on alkane molecules. In general, the more branches the molecule has, the smaller its area of contact with other molecules, and the weaker the van der Waals’ forces become.

These three alkanes have the same molecular formula, C5H12. The unbranched alkane has a higher boiling point than the branched alkanes with the same number of carbon atoms.

Hydrogen bonds

Hydrogen bonds are permanent dipole–dipole forces that happen in particular circumstances. They are the strongest type of intermolecular force and are about 10% of the strength of a covalent bond. Hydrogen bonds will form if

- A molecule contains a hydrogen atom covalently bonded to a nitrogen, oxygen or fluorine atom, and

- There is a lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen, oxygen or fluorine atom.

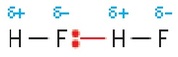

Nitrogen, oxygen, and fluorine are the three of the four most electronegative elements. They form a very polar covalent bond with hydrogen. The single electron in the hydrogen atom is drawn away. The hydrogen nucleus is strongly attracted to the lone pair of electrons in the nitrogen, oxygen, or fluorine atom in another molecule. A hydrogen bond is formed.

There are hydrogen bonds between hydrogen fluoride molecules. It helps to show the hydrogen bond as a dashed line that ends at a lone pair of electrons on the electronegative element N, O, or F.

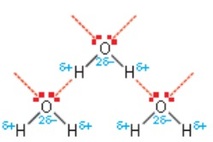

Hydrogen bonding between water molecules.

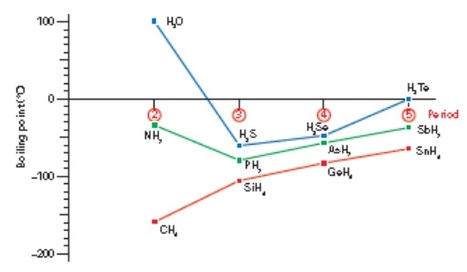

Evidence for Hydrogen Bonding

The presence of hydrogen bonds considerably increases the boiling point of a substance. A plot of the boiling points of Group 4 hydrides shows a steady increase as you go down the group from CH4 to SnH4. This is because the strength of the van der Waals’ forces increases. If you do the same thing for Group 5 hydrides, you see the same trend, except that ammonia NH3 has a much higher boiling point than expected. This is because of the presence of hydrogen bonds. The boiling point of water compared to the other Group 6 hydrides is also much higher than expected. Water has hydrogen bonds, too.

Water and ammonia have anomalously high boiling points. This is due to the presence of hydrogen bonds between their molecules.

The Structure of Ice

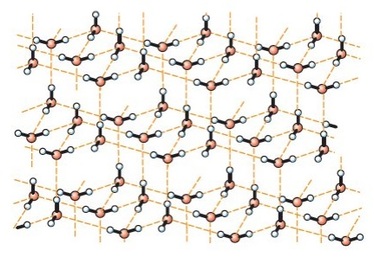

The water molecule contains two hydrogen atoms covalently bonded to an oxygen atom. The oxygen atom has two lone pairs of electrons, so water can form hydrogen bonds. These form along the same axis as the H–O bond on the neighbouring water molecule. As a result, ice has a regular open lattice structure. The water molecules are actually further apart than they are in liquid water, so ice has a lower density than liquid water. This is an unusual property, and explains why icebergs float instead of sink.

In ice, the water molecules are held in a regular open lattice by hydrogen bonds.

Heating solids, liquids and gases

Melting: When a solid is heated, its particles gain energy. They vibrate increasingly vigorously and the temperature of the solid increases. At the melting point, Tm, the supplied energy is used to break some of the bonds between the particles. The structure of the solid breaks down and the particles become free to move around each other. A liquid has formed.

Evaporating: When a liquid is heated, its particles gain energy. They move around each other increasingly vigorously and the temperature of the liquid increases. Some particles at the surface of the liquid may have enough energy to break all the bonds keeping them in the liquid. They will escape from the liquid as separate particles, forming a gas. Evaporation can happen at temperatures below the boiling point, Tb.

Boiling: At the boiling point, bubbles of vapour form inside the liquid, not just at the surface. The supplied energy is used to break all of the bonds between the particles in the liquid. The liquid is evaporating as fast as it can. When the liquid has boiled, the temperature of the gas rises if it is heated.

Ionic, Metallic and Covalent structures

Ionic, metallic, and giant covalent substances have high melting and boiling points. Molecular substances have low melting and boiling points.

Ionic substances: Ionic substances contain ions. Oppositely charged ions are attracted to each other by electrostatic forces. These ionic bonds are strong, and there are very many of them. A lot of energy is needed to break some of them so that an ionic substance can melt. Even more energy is needed to break all the ionic bonds so that an ionic substance can boil.

Metallic substances: Metals consist of a regular lattice of positively charged metal ions, surrounded by delocalized electrons. The metal ions are attracted to the delocalized electrons by electrostatic forces. These metallic bonds are strong and occur throughout the lattice. A lot of energy is needed to break some of them so that a metal can melt. Even more energy is needed to break all the metallic bonds so that a metal can boil.

Giant covalent substances: Giant covalent substances consist of atoms covalently bonded together. These bonds are strong and there are very many of them. A lot of energy is needed to break them, so the melting and boiling points of giant covalent substances is very high.

Molecular substances: Simple molecular substances consist of molecules attracted to each other by weak intermolecular forces. It is these forces that are overcome when a simple molecular substance melts or boils. Relatively little energy is needed to break some of them, so the melting points of simple molecular substances are low. For example, oxygen melts at −218°C and water at 0°C. The strong covalent bonds between the individual atoms in a molecule are not broken when a simple molecular substance melts or boils. More energy is needed to break all the intermolecular forces in a liquid molecular substance. This is still relatively low, so the boiling points of simple molecular substances are low. For example, oxygen boils at −183°C and water at 100°C. Remember that substances that contain permanent dipole– dipole forces, or hydrogen bonds, are likely to have higher melting and boiling points than those with just van der Waals’ forces.